The Challenge

There comes a time in your life when you’re fully at peace with the idea of letting go of your youth and bowing away for a younger, more-promising talent to step into the spotlight as you fade to black. It’s the right, mature thing to do – the “high road”. May of 2007 was not my time to do that.

It all started during a casual conversation with my sister, discussing upcoming family events, future gift ideas for the parents, what funny thing my dog did earlier that day. It was somewhere in the minutiae of this list that she casually dropped in that my nephew had recently been timed under seven minutes in the mile during Field Days, or whatever they do these days to get kids to take home more ribbons. This caused me to pause in thought as she moved on to another topic, to which I wasn’t listening.

“Hold it,” I broke in. “Did you say under seven minutes in the mile?”

“Yes. Like 6:45, I think.”

“Wait. You think, or you know?”

“I know, I think.” She started second guessing herself feeling the weight of my doubt on the other end of the line. “Why, does that not sound right?”

“How old is he? Eight?” I asked.

“Nine. You don’t know your nephew’s age?”

“How tall is that kid?” I asked, ignoring her previous dig at my familial wherewithal.

“I don’t know, like right at my shoulder?”

“You don’t know how tall your son is?”

“Do you think I’m wrong about that time, because I’m pretty sure I’m right?”

“It just seems way too fast for a kid with such short legs. I remember having to run a six-minute mile in high school to be a running back in football, and it almost killed me. And I was as tall then as I am now. I don’t doubt that he could do it with his lungs; it’s just the length of his stride. He’d be taking three strides to every one of a full-grown person. Just doesn’t sound possible.”

“Well, I’ll check it, but I think I’m r…”

“Yeah, check it,” I busted in. I was irritated, and I couldn’t control myself.

It was right about there that I made a horrible mistake. Once again she started a new topic. She got about five words out before I cut her off again.

“Bullshit.”

And then it got worse.

“I would beat Chase in a mile race; that much I know. I have no idea how fast I can run the mile anymore. Who runs just a mile?” I was peacocking for reasons unknown. “But I can’t imagine a scenario that a kid that short would beat me running a mile.”

“Do you think you could run under a seven-minute pace?” she asked, starting to worry that she may have gotten a number wrong in her reporting.

“I have no earthly idea, honestly,” I answered, ” but I’m confident that if I can’t, he can’t.”

I’d gone down a road with no exit ramp, so I did what any levelheaded person would do: I kept going.

“There’s just no way. There’s no way I ran as fast when I was his age as when I was in high school. No way. And I’m in better shape now than when I was in high school.

“So, if I’m right…,” she began.

“You can’t be right.”

“But if I am…”

“I’ll race him,” I said.

The Training

“Todd!” a chorus of voices wafted from the speaker on my phone. It was a call from my sister, but there were others, and it sounded like several.

“Hey there,” my sister’s voice stood out, acting as the moderator. “Crimms, Fentons, and a bunch of others are here and we wanted to call to say hello.” I could almost hear the wine spilling out of the glasses.

This was followed by salutations from various voices – cousins, nieces, neighbors, strangers.

“Is it my birthday? Are you all about to sing to me?” I had no idea why they were calling.

“Hey, Todd, it’s Cristi (A cousin from my father’s side). We’ve been talking about your race with Chase. You know you have to let him win.”

And there it was. I should have known. After finding out that my sister was correct in her reporting on my nephew, the “Flash of Field Days,” I’d been the target of a systematic process of manipulation. Everyone involved in any of the discussions had a strong opinion about what the right thing to do would be. Somewhere in the depths of my psyche it perturbed me that this was even being discussed! To me, it was as clear as a freshly-wiped lens.

“You all are nuts, you know that?” I began to rant. “Assuming that I can even beat him, which at this point I’ll concede as an unknown, you understand that if I don’t, if this kid beats me in a mile race, it’s the end of our generation in this family! I am the only hope we have, no offense to anyone that might be sitting there.” With that there was laughter mixed with more mumbling and party noises – a cork pulled, a glass clinked, something large hit the floor.

I continued on my soapbox.

“I want you all to listen closely, because I’ve thought a lot about this. I’m going to give this race my all; and if he beats me, I’ll accept it knowing that I did. But if it comes to the finish and I can win it, I promise you, I’m taking him down.”

“He’s only nine, Todd,” a voice echoed from somewhere deeper in the room. “You’re going to shatter his confidence if you beat him.”

“And one of these days, you’ll thank me for it.” I hung up.

~

The early-morning sun burned off the bricks of the university buildings in the distance as I stretched in the wet grass alongside the track. Pieces of the Auburn University track team had just finished their workout and were giving me odd glances as they gathered their things and hustled off. The only 35-year-old they’d seen on this track was probably the one cutting the grass.

The race was three weeks away. Until now I had simply kept up my normal running and general exercise regimen – maybe with a few added miles here and there to make myself feel better about my overall fitness level. I still hadn’t attempted a solitary mile. Even though the one-mile distance is less than my normal runs, the problem is the pacing. I was accustomed to running eight-minute to eight-and-a-half-minute miles depending on the overall distance. I could run quite a few at that pace. Upping that to a six-and-a-half-minute pace, however, was a daunting thought even if only for one mile.

I decided to start with a seven-minute pace to see where I was. I loaded two songs on my mp3 player that together equalled exactly seven minutes. I would need to keep on a one-minute forty-five-second pace for each of four laps.

Press play. Run.

I was good through the first lap – checking my time at the start line, I was five seconds ahead of pace. On the second lap, I gave those five seconds back. On the third lap, I lost a few more seconds; and on the last lap, I was able to sprint the last fifty meters to gain the time back and finish about the end of the second song. Exhausted. Seven-minute pace. I was upright at the finish, which I was happy, but I still needed to shave at least thirty seconds. Thankfully, I had three weeks to figure that out. In that moment, however, I had no idea how.

The Race

I hear it a lot: “You don’t seem to age. How do you do it?”. I don’t have an answer for it, but I’ll happily accept the compliment. What most people don’t see is the pain incessantly lingering underneath. I may not age fast on the outside, and my maturity level has been questioned from time to time; but I’m convinced that any extra youth filtering to these areas has been sapped from my muscles, bones, and joints. Playing hard takes its toll, as do the miles and miles of pounding my body has endured over the years of my exercising away the typical results of unhealthy lifestyle choices. I wince when standing up and sitting down; I just hide it well.

When the day arrived I was as ready as someone my age could ever convince himself to be. Mentally, I was solid. No matter how much my sister and the rest of my family attempted to convince me otherwise, I still believed my logic was sound: my stride was too long for him to out-kick me in the end. As long as it was close, I would finish first.

The Race was all I thought about that day. From the moment I painfully rolled out of bed until the start, I stayed focused, even though it was just one event in a day of family activity. The extended family had descended upon Princeton, Indiana, and my childhood home for Mother’s Day. This gave me a home-field advantage of sorts. The Race would take place in the late afternoon, and the location was my high-school track where I spent years running in circles for every imaginable small-town sport, including track and field. In my mind, everything was slanted in my favor. All this withstanding, I was haunted by one aspect of the day that was spotlit in my eyes: Why was Chase so relaxed?

From the moment I woke up, I was stretching and hydrating like an Olympian. I ate all the right things and was pacing through my food and beverage intake thoughtfully. Chase on the other hand had a soda in one hand and one of my grandmother’s brownies in the other at all times. The only time he didn’t was when he was roughhousing in the yard or rounding the bases during a pick-up whiffle-ball game.

He was running amok, an eternally-lit soft drink the flame in his hand. A child’s energy, unstoppable it seemed. Aggressive wanderlust about the yard. Balls of all types rocketed with meaningless direction. Kids fell down, got back up, screamed, laughed. What race?

I was torn between whether the scene should worry or elate me. Would he wear himself down to nothing, a dim ball of expired fire? Was this his way into my head? Was he manipulating my emotions? Was this, dare I say, a mind game? Was he even mature enough to understand mind games? Did it even matter? I mean, here I was expelling my mental energy trying to break down the scene. Did he get to me without even trying?

I shook my head and made my way back inside avoiding a few more cousins and their endless pleas to get me to throw the race. One more water. Maybe a banana. One hour left before the gun.

We had to take multiple cars to the track. The crowd seemed to grow as the time drew near; and if there’s one thing I didn’t need, it was to have my limbs balled up in the back seat of an over-capacity car. I was dressed in a full warm-up suit with Chase walking beside me wearing the same clothes he’d been playing in all day. No special shoes. No running-specific attire. No care in the world. I looked like Rocky entering the ring before fighting Clubber Lang! Laser focus. Unflappable. At least that was the scene I chose to project. Truthfully, I had no idea what was about to happen.

I had one more mental play, and now was the time to pull it out. Adjacent to the track is an out building with restrooms and a concession stand, but there was only one part of the out-building that would play a part in today’s festivities: the posted Princeton Community School District Track & Field Wall of Fame (I may be making that name up).

Regardless of what it’s called, there’s a young man’s name etched there that holds one of the area’s oldest records. It was for an event that would make no difference today, and it was set when my back felt a lot less like a champagne flute than it did on the day of The Race, but I figured it was worth the intended rub at my opponent:

I’m an established homer at this track. Never mind that my record was set in the pole vault, 20-25 more people than are present today used to chant my name. You can still hear them – if you’ve had as much to drink as every adult there that day but me.

I think at the time Chase thought it was pretty cool, which gave me a boost of confidence. And honestly, the small amount of respect it commanded did bathe away some of my angst over this entire endeavor. I still was unable to convince anyone of middle age in my family the importance of my winning. It just wouldn’t land. So a part of me at that moment opened to the possibility of my losing, and what my legacy could possibly be after that loss. 1) I was the only one in my family who had a chance, and 2) I still held that record. The fact that the sport of pole vaulting was discontinued in Princeton shortly after I set the mark wasn’t something I felt necessary to share with the rest of the group.

The start line felt familiar, and I was confident in the beginning. I wasn’t sure what Chase’s strategy would be, or if he even had one. But I knew mine, and I was going to stay the course.

Everyone in attendance gathered around the start line. With a smooth flurry, I jettisoned my outer garments like a magician casting a dramatic effect on an unsuspecting crowd. There I was, a billboard subject for Nike – a futuristic ensemble that wouldn’t make a wave until the next Olympics. Compression athletic wear before it was mainstream. I looked the part. I was grasping to belong. My back ached as I bent forward waiting on the go. Final “good lucks” were addressed to Chase.

On your mark, get set, go…

The first quarter of a lap went as I expected. Chase stepped his pace out to front me, half of it his effort and the other half mine to give it to him. I would draft off him as long as he wanted to lead (as much as you can possibly draft off someone that size). I assumed I would be able to keep up with his pace. All I needed to do in my mind was be a few steps behind him with around two-hundred yards left to out kick him. His pace surprised me, but it was manageable. His only hope was to leave me behind with no distance to catch up. Lap one had me behind him by a few feet, so things looked good.

As we cleared the crowd and started rounding the second corner of lap two, Chase’s pace started to taper back a bit. I found myself on his heels having set my pace mentally and not adjusting right away when he slowed. As much as this sounds like a good thing for me (and I’ll admit I felt a wave of relief when I saw it), it wasn’t a good thing. I felt compelled to keep my pace, so I upped it casually to complete the pass and planned to then settle back just in front of him. In my mind, he was slowing; and I could possibly put this away once I was the front-runner. This was a mistake. The second he saw me edging forward on his right side, he simply adjusted his pace and shot right back in front – an effortless, very scary adjustment. I had used stored energy on that pass, and he simply kicked forward without feeling. He didn’t understand pace because he didn’t have to. He could just change at will. Bad news.

The rest of lap two and all of lap three remained the same. He stayed just in front of me, so my plan was still intact. I was haunted by that adjustment though, and those were a wearing two laps of a mental battle. His fluid speed increase to block my pass had the look of a runner that wasn’t going to easily be out-kicked. My confidence fleeted away a little more with each labored breath. As we passed what would become the finish line on the next go around, Chase’s coach, my brother-in-law Matt, yelled a final cryptic message to his athlete.

“Remember what I told you about this final lap!”

Son of a bitch. There was a strategy in the other camp.

Chase increased his pace as the “bell lap” began. Cheers for seemingly anyone but me sprayed from the stands. Another beer can popped.

Matt clearly knew my intention to sprint out the last two-hundred meters, so their plan was to wear me out during the first two-hundred by increasing the pace and leaving me with nothing left for the kick. It was the right call. I was dying. If I didn’t stay right on his heels, I was finished. That was the easiest of two tall orders. The hard part, if I didn’t collapse before I got to the 200-meter mark, would be passing him and sprinting through the final turn and homestretch.

I made it to the 200 mark without losing ground by some triumph of the human spirit. I refused to give in to the pain that was radiating through me like my wet finger was stuck in a socket.

Lengthen your stride to the max and pass him.

Just as my legs processed the signal from my brain, Matt’s distant shout from the finish line chilled whatever was left of my bones. More strategy. More premeditation. More bad news!

“NOW! NOW, CHASE, NOW!”

Chase started to sprint. And I started to sprint. We were side by side rounding the turn, and all I could think about was how I couldn’t hear him breathing at all. But then, something came over me that I desperately needed at that moment – a gift from somewhere unknown, because I certainly didn’t have any friends in that moment at the track. A second wind.

I remembered my initial thought when this debacle began, and I honestly still believed it. I was wrong about it not being possible for a kid his age to run a mile that fast – that was evident. But there was still one thing I said to my sister that day that I didn’t have to concede just yet.

“I don’t doubt that he could do it with his lungs, it’s just the length of his stride. He would be taking three strides to every one of a full-grown person. Just doesn’t sound possible.”

He couldn’t win it unless I lost it. We were even with 200 meters to go, and I had the advantage. But did I have the lungs? The endurance?

I couldn’t hear him breathing, but I could hear his footfalls, and they were double mine. I was right. I stretched my length as much as I could, and mustered everything I had left to sprint out the mile. I lifted onto my toes and slowly gained distance.

“Chase! Chase! Chase! Chase!” thundered from the stands as the homestretch started to slide under our feet. I completed the pass and glided in front of him. I tucked my head and hoped for the best, assuming something would tear or pop or explode through my skin and onto the track at any second. I expected him to pull up beside me and then around me, putting me out of my misery, but it didn’t happen.

And then it was over.

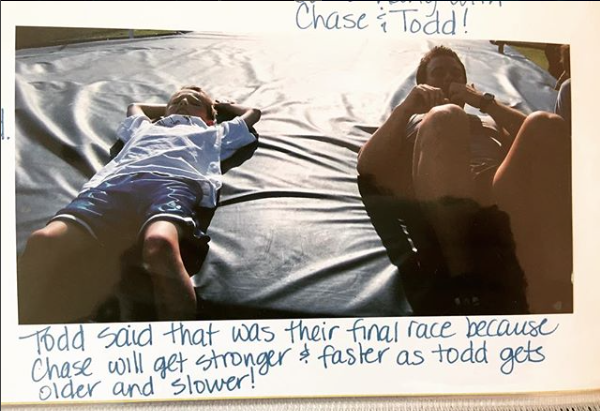

I crossed at 6:27 and Chase just a few seconds behind me. I fell into the pole-vault pit lifeless and pain-ridden as the crowd huddled around Chase and possibly hoisted him onto their shoulders – my memory is hazy on the subject. I do know that he eventually made his way over to the pit and fell down beside me.

“I retire,” I said between heavy pants. “We’re never racing again.”

“Deal,” he said.

The Legacy

Today at family gatherings it isn’t uncommon to overhear me telling the story of that day and shamelessly reminding everyone that Chase’s current success in athletics can be linked back to my original challenge and the drive cultivated by his desire to beat his “cool uncle” in a race. I’m the one writing this story so I can add whatever adjectives I feel apply.

It was wise of me to retire on top. Until very recently, Chase ran both track and cross country for the University of Arizona, but his real talent is featured on the international triathlon circuit. He was offered a new opportunity with Project Podium, an elite triathlon squad run by USA Triathlon in collaboration with Arizona State University with the goal of producing triathletes for the U.S. Olympic team.

I was standing with my sister and Matt at the finish line when Chase crossed placing twelfth in the world and first American in his age group at the ITU World Triathlon Finals in Rotterdam in September of 2017. His mile pace was well below seven minutes, by the way.

I invite everyone to follow Chase on his dream of making the Olympic team (Check below for social media info). I believe he can do it. I also believe that “The Race” fueled his desire to never finish behind anyone. Had I let him win, he’d be thirty-pounds overweight lying somewhere on a couch with all my relatives blaming me for his gluttony! Right?

Follow Project Podium on Facebook